The Power of (a Child's) Observation

Montessori in Real Life

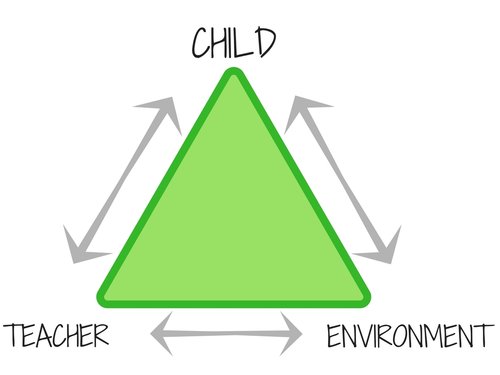

So often in Montessori we talk about the value of observation as it pertains to adults observing children. While it is important to take a step back and observe our children as they work, it is equally valuable for our children to observe us, and each other. Children, from the time they are born, are skilled observers. How incredible is it that babies learn simply by being and observing? They typically do not need to be taught to talk and play and walk - they simply watch and learn. With three children, I’ve had an abundance of opportunities to observe how they observe…

Many children are observers when they are somewhere new, and that is especially true for D and S. It hasn’t always been easy for me to watch them not jump in and try new things or “join the fun”. I have to remind myself that while many children learn best by doing, some children learn best by first observing. Our job is to provide opportunities and a safe base from which to explore, and their job is to trust themselves to decide when to dive in, or not.

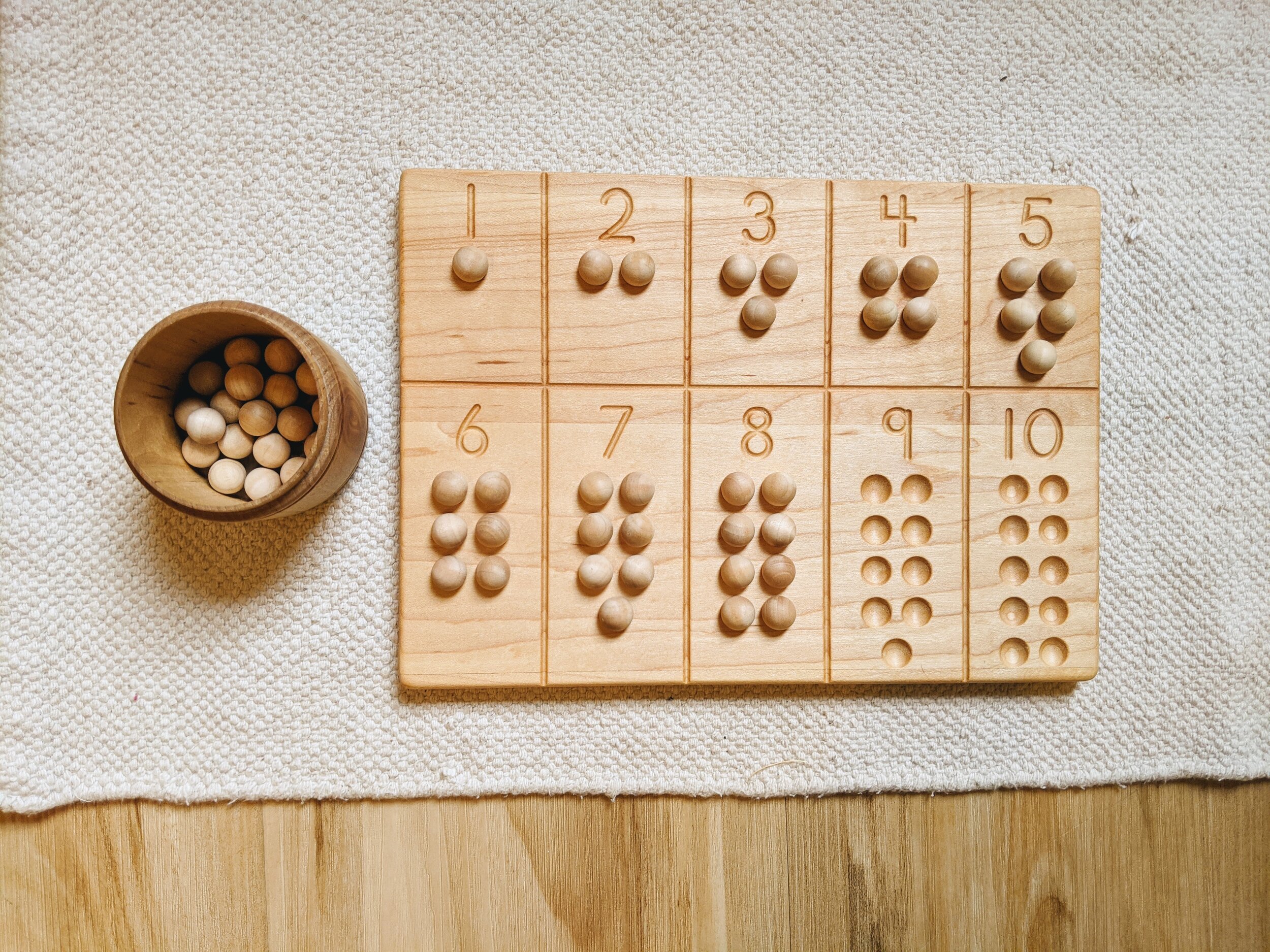

S (3) is in his first year of primary and has spent the majority of his first month observing. He stays close to his teacher and watches her give lessons and the children work. Even so, there has been no shortage in learning. I can see how much he’s absorbed through observation when he comes home and gets to work here. He goes to our playroom and unrolls and rolls rugs on repeat. He traces letters and makes different letter sounds. He sings the songs he’s learned on repeat. He meticulously chops carrot sticks from his lunch box “the way my teacher does it”. Observation is education.

D started primary in the exact same way. Now in her third (kinder) year of primary, she simply dove into work on day one. It is beautiful to see her growth each year in the same classroom. This doesn’t mean she has stopped observing. As most children do, she observes before and as she works. I see this observation play out through her pretend play at home. We come home from school and she immediately dives into playing school with her stuffed animals, acting out whatever she observed that day. Observation leads to deep pretend play as a way to process the day’s events.

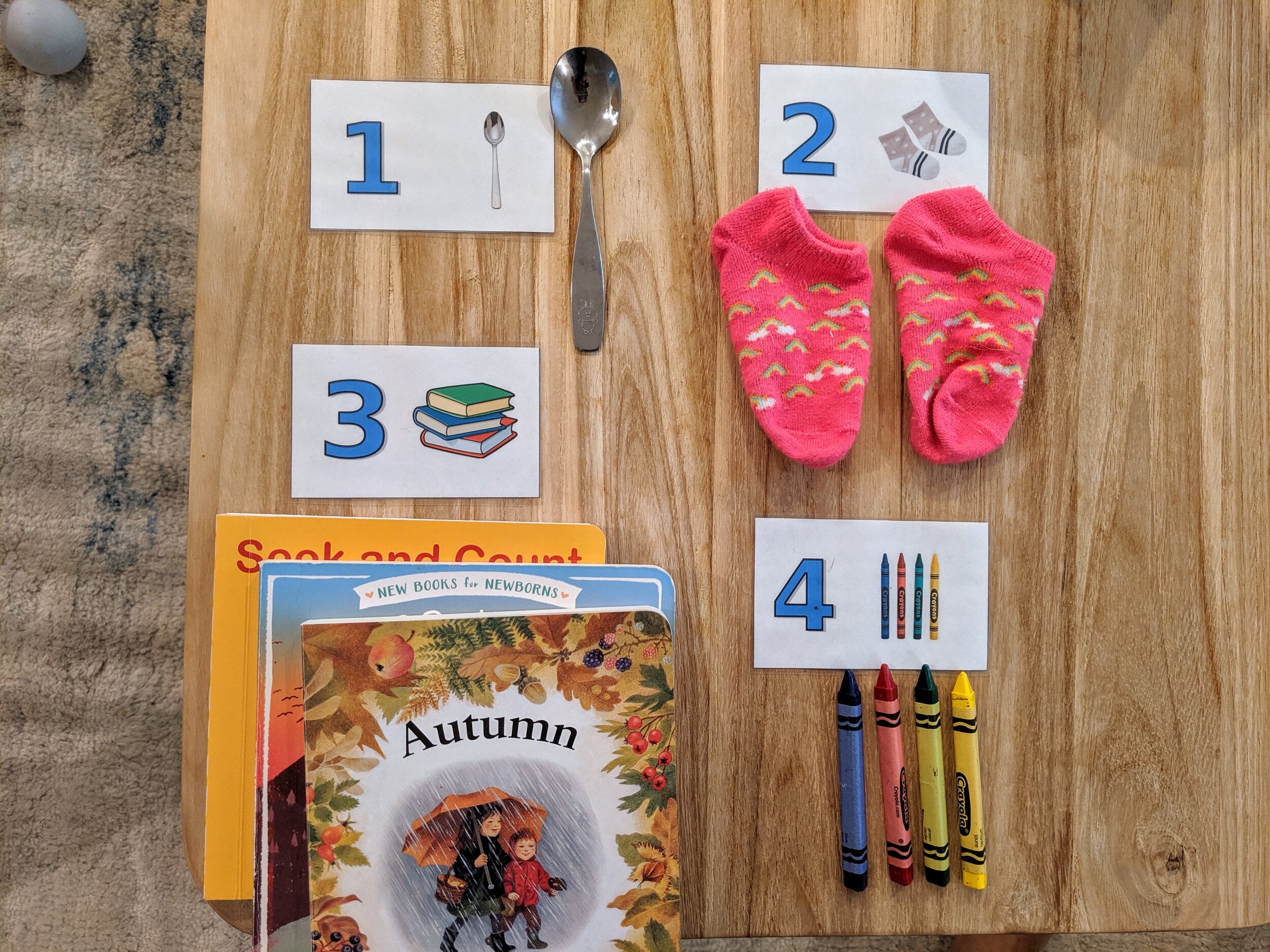

Birth order plays a role too. While D, as the oldest, mostly learned by observing adults as a baby, S and J learn so much by observing each other. I remember when S was a young toddler and I introduced the kitchen knife, I didn’t even need to give him a lesson. He picked it up, held it correctly, and began chopping just as he’d seen D do many times before. J, observing his older siblings sing in the car at the top of their lungs, has already learned how to coo loudly along with them. He’s also quite eager to crawl right after them as they play, seeing just what opportunities movement can offer him. Observation is a key piece of multi-age environments.

Children’s sharp observation skills can also serve as a reminder of the importance of modeling. If we would like our child to hang up their coat, we have to do so ourselves first. Simply asking or saying the words isn’t enough. When we model something over and over, they pick up on it simply by observing that action again and again. The other weekend my husband decided to build the kids a mud pit so they’d focus their digging in a designated spot. When he asked if they wanted to help, they initially said no, but once they observed him out there with his tools, they were eager to join in. Observation is often more powerful than listening.

Observation is important for us all. It can be tempting to jump right in and fix something for our child just as it can be hard to watch them sit on the sidelines. But I have learned time and time again that pushing to “do” doesn’t get anyone anywhere. Many people, both children and adults, need the space and time to take in their surroundings by watching and listening first.

Observation isn’t what comes before the work - it is the work.